Today, there is little doubt that a peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine will reflect power politics. Ukraine will have to give up territory in exchange for – as many warn – a fragile peace. We asked international relations expert Dr Igor Kovač to comment on the case.

“Perhaps rightly, we are under the impression that such a deal is not fair. But international relations are relations of power. Thucydides already wrote 2500 years ago that the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. This is still true today,” believes Dr Igor Kovač.

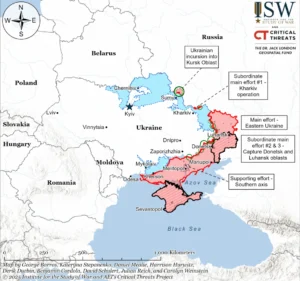

So, what are Ukraine’s prospects? In return for peace or a freeze in battle lines, it would get security guarantees from European countries, and perhaps some non-European ones, too. The return of a small part of the territory to the Kharkiv oblast, free navigation on the Dnieper and help in rebuilding the country.

Russia would have gotten a much better part of the deal. The US would de jure recognise Crimea as part of Russia, while de facto recognising Russian control of the occupied territory in the east of Ukraine, that is, parts of Lugansk, Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. Sanctions imposed since 2014 would be lifted, and economic cooperation between the US and Russia would increase, especially in the energy and industrial sectors, Axios reports.

How the US recognised Russia’s superpower status

As Dr Kovač pointed out, the final version of the agreement will be slightly different, as “we can say with certainty that not all of this will be in the final agreement, as negotiations are currently underway.”

How much longer will the negotiations continue? He pointed out that, although such predictions are ungrateful, they are likely to last for another month or two, according to our interlocutor.

“About two months ago, when Donald Trump took over the leadership of the US and then started to look for a way to peace in Ukraine, we estimated that the latter would be achieved by Easter. Unfortunately, this did not happen because Russia insisted that the parties negotiate not only a ceasefire, as was the US starting point, but also a broader peace deal. This extended the timeline. The US made the right decision to put itself diplomatically between Ukraine and Russia, thus recognising the latter’s superpower status. Unfortunately, this opened up the possibility of delaying by Russia, which it has cleverly exploited with the aforementioned approach. All this is now slowly coming to an end. The US is losing patience, and we are close to an ultimatum,” explained Kovač.

According to the information available so far, he estimated that Russia will continue to delay accepting the terms of the peace agreement until the US imposes secondary sanctions, further arms Ukraine, and then the Kremlin gives in. As has already been said, this could happen in a month or two.

International law and political reality

On the other hand, critics of the course of the negotiations point out that the recognition of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of four regions in eastern Ukraine is not in line with the foundations of international law. It is in direct contradiction with the Charter of the United Nations, the Helsinki Final Act, as well as the so-called Crimea Declaration of 2018, i.e. a document from the Trump administration. It says: “In accordance with the principles expressed in the Welles Declaration from 1940, the United States reaffirms as policy its refusal to recognise the Kremlin’s claims of sovereignty over territory seized by force in contravention of international law. In concert with allies, partners, and the international community, the United States rejects Russia’s attempted annexation of Crimea and pledges to maintain this policy until Ukraine’s territorial integrity is restored.”

Kovač responded to this, saying: “Before moralising about the US position, let’s see what Europe’s position is (was). Macron called on Ukraine to give up territory for peace in 2022. He has repeated something similar now, calling on Ukraine to behave realistically. In February 2022, most European leaders and Eurocrats did not think Ukraine could withstand an attack from Russia and were therefore reluctant to come to the rescue. They were more concerned about how to smooth relations with Russia ‘in three weeks’. Ukraine was saved by the US and US private companies. Moralising of any kind never solves the situation and is, therefore, not politically productive. I think that Europe has now understood this, and is thus also becoming an active and constructive part of the negotiations and of the security guarantees for Ukraine. This also lessens the transatlantic divide, both politically, as well as economically and militarily.”

Žiga Korsika