In a Poland devastated by the war and with a population very reluctant to accept the government imposed by Stalin, the communists decided to show the Polish people the excellencies of the socialist paradise. With the support of the Soviet Union, they decided to build a new city very close to Kraków. Thus, on 17 May 1947, the Nowa Huta project was born, although construction of the first flat blocks did not begin until June 1949. The town was to house the more than 30,000 workers who were to work in a new steel plant, the Lenin Steelworks, built between 1950 and 1954.

Working conditions were not easy, and in order to encourage construction and enlist volunteer workers, the communists turned to a stakhanovist figure, Piotr Ożański, a worker so class-conscious that he allegedly managed the feat of laying 33,000 bricks in a single day. Despite the difficulties, Nowa Huta became a reality.

Following “socialist realism”, Nowa Huta had a huge central square, presided over between 1973 and 1989 by a huge statue of Lenin, from which five wide, tree-lined avenues branched out to represent the five points of the red star. There were also parks and even lakes, but no church. According to communist logic, the workers did not need God because they already had the Party.

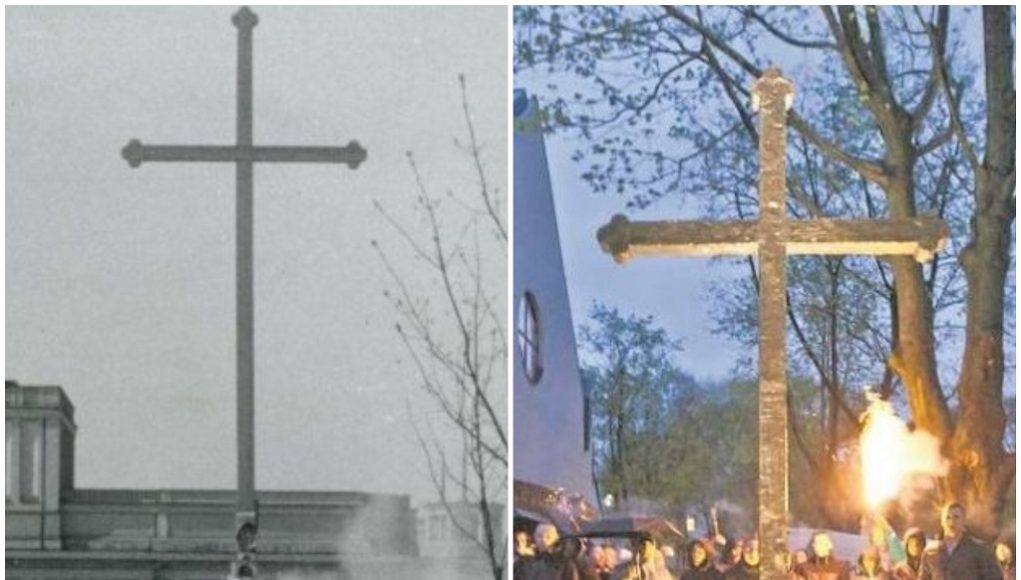

However, in 1956, after the protests in Poznań and the death of Stalin and the Polish communist leader Bierut, the so-called “Gomułka thaw” took place. The new General Secretary Władysław Gomułka abandoned Stalinism and enacted some reforms. In Nowa Huta, the authorities allowed the construction of a church in 1958 and the faithful erected a wooden cross on the chosen site. A place where, from that moment on, mass began to be celebrated. But as expected, communist tolerance of the Catholic Church did not last long and the Party changed its mind. Nowa Huta did not need a church, but a school to teach Marxist values. Karol Wojtyła, auxiliary bishop of Kraków and future pope, tried to convince the authorities, but the Party’s decision was irreversible.

On the morning of 27 April 1960, a group of workers was sent to remove the cross, but was prevented from doing so by passers-by. Gradually, an increasing number of people began to gather to defend the cross. Faced with such a challenge, the authorities sent in the militia to put an end to the protest so that the cross could be taken down. The militia used truncheons and tear gas, which were met with stone-throwing by the protesters, and a pitched battle ensued that lasted until nightfall.

A few days later, Gomułka called the defenders of the cross “scum” and “troublemakers”. As a result of the riots, the Militia drew up a list of over two hundred people to be imprisoned, fined or dismissed from their jobs. However, the Cross remained. The protests continued, albeit peacefully thanks to the intervention of Karol Wojtyła, and in 1967 the authorities allowed the construction of the new church, which was built by the workers of Nowa Huta over a period of ten years.

Nowa Huta is now a neighbourhood of Kraków, home to almost a quarter of a million people. The central square was renamed “Ronald Reagan Central Square” in 2004 and houses a monument to the anti-communist workers’ union Solidarity (the statue of Lenin was dismantled in 1989 to the applause of Nowa Huta citizens). Next to the Cross, the symbol of resistance, a church, the Ark of the Lord (Kościół Arka Pana) was erected, which was finally consecrated in 1977 by the then Cardinal Wojtyła. Thanks to those who were not afraid, the Cross was victorious again.

Source: El Correo de España

By Álvaro Peñas