With the former archbishop of Ljubljana, cardinal prof. Dr Franz Rode, we spoke for the needs of the show Beremo on Nova24TV in the House of St. Jožef in Celje. The conversation took place about his interesting and comprehensive book, entitled Vse je dar (Everything is a Gift) with the subtitle Spomini (Memories). He presented us with his journey, what his position is towards the Church in Slovenia, and we also spoke about politics. Since the conversation is also interesting for the readers of Demokracija magazine, we are publishing the magnetogram of this picturesque and sparkling conversation on this site.

Berlec: Mr. Cardinal, Mr. Dr Rode, I would like to start with a classic question. Why did you decide to write a memoir? I suppose because you had, because you really have a lot to say… Maybe also because you lived a memorable cosmopolitan life? Because you were a high church dignitary for decades, not only in Slovenia, but especially in Rome, in the Vatican…

Rode: You are actually answering for me. I agree that my life has been very rich, but also very interesting and complicated. I left Slovenia as a child with my family at the age of ten, spent a long time in camps in Austria and then seven years in Argentina, one year in Rome, and eight years in France, where I was very full of plans. The decision to return to Slovenia was not easy, as there was a dictatorial one-party system that was not in favour of Christianity. Nevertheless, I decided to return, in fact, it was the call of the earth. I knew that if I wanted to be an authentic person, I also had to be an authentic Slovenian. That is why I decided to go to work in Slovenia as a priest, where I established myself as a professor at the Faculty of Theology in Ljubljana for more than 16 years, which were extremely rich and beautiful years. I was fluent in several languages and had a broad horizon on modern issues, especially on modern atheism. I was called to Rome, where I was again for 16 years. I travelled the world, saw practically every continent. The appointment as Archbishop of Ljubljana surprised me. I was an archbishop for seven years and I accepted this job with a great sense of responsibility, as well as with pleasure. Not out of any vanity, but as a mission that is probably in God’s plan. I carried out the mission with all my strength, with all my heart, with all my talents, but also with all my limitations. I was happy and fortunate that God took me to this ministry.

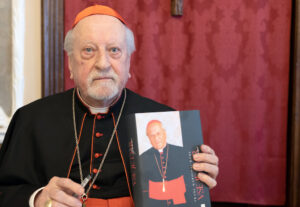

Then John Paul II called me to Rome, where I became prefect of the Congregation for Religious. A year later, Pope Benedict XVI appointed me cardinal, I was the second cardinal in Slovenian history.

Berlec: In the introduction to the book, you wrote that you showed yourself as you are: “with a living and active memory of the youthful awakening under the Southern Cross and with the luxury of French culture, with the Augustinian discovery of God as beauty and the conception of the Church as a place of freedom”. In doing so, you had before your eyes the rule set by Pope Leo XIII for the chronicler, I quote: “that one should not say anything false, that one should not keep silent about anything true, that one should avoid the suspicion of partiality or concealment when writing”. Having said that, you wrote that this is undoubtedly a demanding rule!?

Rode: This is a perfect rule for any historian and anyone who writes about himself, to say nothing false, to conceal nothing telling, and to be completely honest. In my memoirs, I also mention that there are things about which it seems impossible to say everything. Some things seemed to me unimportant or unnecessary to tell, because I would probably insult or hurt some people in our Slovenian environment. I think this is a rule of Christian love and also life wisdom. It is not wise to accumulate new opponents with our words and statements.

Berlec: Let’s turn to your life story. You are at home from Rodica near Domžale. The writer Alojz Rebula described your family as a “classic solid Christian family”. As you wrote in your book, your family has been settled in Gorenjska region since at least the 16th century, and you delved deeper into your roots.

Rode: I was very interested in who we are and where we come from, also where the surname Rode comes from, which is mainly present in the Kamnik valley. Furthermore, I also discovered several Rode surnames in Saxony, Norway, and elsewhere. So, in the European area. In fact, as far as I managed to discover, our story begins in the 16th century, around 1530. The first surname was recorded in the Menge parish as Sebastjan Rode, who was baptised on January 8th, 1514. The same year that Trubar’s Christian Bible was published in Slovenian. Since then, we have a certain clear historical genealogy. Ancestors were reported among Slovenian men and women.

Berlec: You came into the world in September 1934 as the seventh child. In the book, you wrote that the upbringing in the family in which you grew up was based on the solid foundations of God’s commandments, the teachings of the Church, and sound common principles that were preserved from generation to generation.

Rode: Undoubtedly, Christianity was received by the majority of Slovenian families in those times. When, a few years later, I found myself in a foreign, completely different, say, South American world with a different language and mentality, Slovenian Catholicism, the Slovenian form of religion, somehow seemed too narrow to me. I experienced a crisis of faith, if you will, which was not in the sense that I rejected my faith, rejected God, but I had to review what I believe and how to come to a better, more acceptable image of the God in whom I believe. It was an internal process that was painful at times, but which led me, I hope, to some mature faith, which is something very positive in my life.

Berlec: Undoubtedly, your family, like many Slovenian families, was strongly marked by the Second World War, that is, the occupation and then especially the communist revolution. Your memories of that time are very vivid. In the book, you wrote that after July 22nd, 1941, the apparent calm that began with the German occupation in April 1941 ended. To quote you: “Of course I did not know that on that day Hitler broke the agreement with Stalin and attacked the Soviet Union. In Rodica and in Jarše, some left-leaning families, who welcomed the arrival of the Germans by hanging giant Nazi flags, quickly hid these flags. It started to be said about some gošars or gmajnars (forest men) who were fighting against the German occupation.” Already in September of the same year, you experienced all the tragedy of that time with your own eyes. How was that?

Rode: That is when the mistrust among people actually started. We did not know who these, as we called them, gošars, were, the name partisans came later, hostars as well. In the beginning, there was no antipathy towards them in our family. As far as I know, it was mandatory to give some wheat, butter, even some cows, etc to the partisans. After they began to fall and it was proven that they were murdered by partisans, this split in the Slovenian nation, a rift, began. For example, one of our uncles from Bišče, Franc Kokalj, was killed at home by local partisans. They wanted him to go with them, he refused, and they killed him. Why, no one knew. Maybe because the family was a little too much, a little wealthier, or because he just was not with them, because he did not want to be with them. A little later, one Sunday after mass, the church in Mengeš was surrounded by the German army. Soldiers with rifles directed all of us coming from the church to the cemetery, where there was a pile of dead bodies, already decomposing. Some recognised their relatives, fathers, and brothers, they were locals, from our places, all honest people. They were killed by partisans; we did not know why. They were found in a cave in the forest by a poor man who was looking for brushwood. The Germans took the bodies to the cemetery, expecting that people would turn against the partisans who do such things. This marked the beginning of the Slovenian split. It was caused by partisan crimes against completely innocent people. This is how our family, especially my father, cooperated a lot with the partisans in the beginning, and distanced themselves from the Liberation Front, which was constantly being talked about. After that, we at Rodica were believed to be against partisans. Most people, however, retreated in fear and did not define themselves.

Berlec: The next event that marked your family and you personally for the rest of your life was definitely May 8th, 1945. That is when you went into the unknown. You wrote in the book that seventy years later you still wonder how you could make such a fatal decision to leave your native land, your home, to which you were all so strongly attached…

Rode: It was, of course, a very difficult decision. In fact, some Party leaders from our localities also advised us not to leave home, that nothing would happen to us. But we went. My brothers have been with the Home Guard for about the last six months. We retreated to the Austrian Carinthia, thinking it would only be for a few months. We were firmly convinced that we would be home in the fall. If we had known that this was leading us into the world and we would never return, we would not have gone.

Berlec: How did you experience your time in the Austrian refugee camps? In the book, you wrote that it was there that you realised you had a talent for languages, a school was organised…

Rode: With the help of the priests who accompanied us, we used this time very well. For example, there was a high school in Spittal where I was enrolled. I finished two classes, I started the third, then we left. After all, as children we did not feel the weight of being a refugee, but of course our parents felt it very painfully. But we played sports, we studied, we made a lot of friends, the organisations worked, in short, there was no oppressive atmosphere, we lived a happy life.

Berlec: Your next period is tied to life under the Southern Cross. You lived in your new homeland, that is, in Argentina, from 1948 to 1956. And in those years, the decision to become a priest matured in you… How is that?

Rode: The thought of the priesthood has followed me since I can remember. In Rodica, near us, in Groblje, there were Lazarists who had a mission centre. They were very active, there were many activities, exercise, clubs, choirs, theatre, and more. We lived very closely together in this circle of Catholic youth organisations. They were young priests, very dynamic, happy, relaxed, and they became an ideal for me. I remember once saying to one of my neighbours: “If I am not going to be a priest, I am going to be a sexton. I will do something at the church.” Later I was a little more ambitious and said to my neighbour: “Janez, remember. I will be a bishop one time.” (laughs)

Berlec: The fact that you spent several years, especially during your doctoral studies, in France, in Paris, the heart of French culture, undoubtedly left a strong mark on you as a personality. I think you have very fond memories of those years…

Rode: I have inappropriately fonder memories of France than any other country I have lived in, be it Austria, Argentina, or Italy. The breadth of the French spirit and the depth of perception of life as well as the beauty of life, this is very much alive in the French. On the other hand, the French language is something absolutely wonderful. I felt extremely beautiful in the French cultural and spiritual world. I enjoyed French literature, I constantly read their authors and also learned the French language. So, for years and years I wrote and spoke only French.

Berlec: Your decision to return to Slovenia after completing your doctorate in Paris in 1965 is interesting. Your first job was right at St. Jožef in Celje. In other words, at a time when many fled to the democratic West, you returned to your homeland, where a one-party communist regime ruled. This decision was very brave. When you came back, did you also deal with Udba?

Rode: Clearly, Udba was observing me. In Celje, a man called me to talk and asked me about my stay in France. He did not say it was an interrogation. In the conversation, this gentleman or comrade was particularly interested in Mr. Nacet Čretnik, who was our spiritual shepherd in Paris and was considered a great opponent of communism. He asked me what Mr. Čretnik said to me when I was leaving for Slovenia. I said that Čretnik did not like my decision too much. But he gave me advice in Latin: Be careful as serpents and simple as doves. When I quoted this advice to a comrade in Latin, I left him in suspense, he did not understand, and he blushed. Then I told him the saying in Slovenian.

Then they found another way, which did not last long either. The director of Mohor’s company was Pavel Golmajer and he was undoubtedly connected to the Udba, the secret police. He started inviting me here and there to some cured meat or to meet interesting persons in those days. The fairly famous painter Jože Horvat – Jaki lived in Nazarje. We walked around Styria, visited inns, and talked. He always somehow provocatively turned the conversation to politics, for example, what do we think, that the bloodthirsty beast of the Home Guard is preparing another attack on Slovenia. And I answered him: You killed them all. He provoked on purpose, they did not hear anything from me, because I did not have anything to say either. I was not associated with any anti-communist organisation, anywhere. What I said was public. Then they left me alone. But I find the following interesting. In 1973, I went to visit my mother in Argentina. That was my last visit to her. I even gave a lecture in Argentina, and some emigrant circles, say Rudi Juršec and some others, did not like my performances. I expressed myself freely, I said what I thought, my position was in no way fundamentally against the government, even for it. But we were talking more about socialism, which is ultimately acceptable if it is effective. But not in the party. I have always opposed the party.

When I returned to Slovenia, the very next day I received a summons to Mačkova street, near the diocese, where the Ljubljana police was stationed. I called the religious commission, the secretary Peter Kastelic answered. I told him that I will not go to Ozna, I have nothing to say there. I was in Argentina; I spoke freely, and I think I proved that there is freedom in Yugoslavia. But now they will find out that I was called to Ozna, for questioning, and they will spoil the good impression I left in Argentina. I am sorry that you will suffer such damage through your own fault. There was a lot of cynicism on my part. However, on the other hand, they gave up. The next day I got a cancellation of the invitation to talk with the note that they were adding the possibility of a later invitation. They never called me again, from then on, I had peace from Udba.

Berlec: How was it with Grmič, did you have any conversations or anything similar. In Slovenia, he was and still is the so-called red bishop.

Rode: When I came from France, which was considered theologically very advanced, the French Church was ploughing the fallow, new experiments, and new methods. In those years after the council, we did not immediately realise where all this was actually leading. We were in favour of accepting the council, to implement the council’s guidelines, but not to harm the Church and work against it.

Regarding Grmič, we realised that he is actually connected to the Party and that he works against the Church. I am not judging him, but his outward performance turned out like that. So, Truhlar, Perko, Stres, Križnik, and I quickly distanced from Grmič. He was left with Rafko Vodeb, who also left later. This was also done by his close friend Jože Rajhman, and so Grmič was left completely alone and then died very lonely.

Berlec: Of course, with such an extensive book, we cannot go into all the details of your life’s journey. At this point, I will ask you a question that the late writer Alojz Rebula asked you years ago. I quote: “After a few years as a professor in Ljubljana and in Rome in the Council for Culture, you occupied the seat of the Archdiocese of Ljubljana. You occupied it with the temperament of a young free European in the era after the fall of communism, in a time that would be called inertia rather than transition, because behind the formal democratic façade remained the previous regime structure, from the judiciary to education. At that time, in one of the speeches from Brezjan, which was listened to by all of Slovenia, you asked yourself whether Slovenia wanted to remain an island of atheism in Christian Europe. What memories do you have of that time?”

Rode: My episcopate in Ljubljana was in its own way the most important part of my life, the most exposed, the most difficult, and probably the most heroic. Sorry if it sounds too understated. Namely, do you know what the pastoral conscience of one bishop is? You are responsible before God for the nation entrusted to you. You are responsible for saving or destroying so many people. You must see to it that no one will perish through your fault, that no one will leave God because of you. You have to do everything, no matter how much it costs you, to bring as many people as possible to God. I worked from this extremely sharp sense of personal responsibility, episcopal responsibility, and also suffered a lot because of it.

Berlec: In the book, you also write about many events and your actions that did not bear fruit or even damaged your reputation in the public. For example, you cooperated well with Drnovšek. You write that there was a kind of sympathy between the two of you, but you had a much worse relationship with Kučan. The latter did not repay you the tribute you gave him in your speech at the international symposium on the role of Christians in politics. In the book, you wrote at the time: “The priests resented me, people were disappointed, why I did it. I expected that Kučan would repay me this tribute by advocating for atification, but I was mistaken. He did not do anything.”

Rode: That is what it was about. That is when we finished the so-called Slovenian Synod or Slovenian Provincial Plenary Council. It was about the state also recognising what we expect from it in this programme of ours. That the Slovenian state authority will also go towards the Church. I expected that President Kučan would put his word in the context of an agreement between the Church and the state. This led to the Vatican agreement. That he will support this effort of ours for relations with the Holy See. I actually over calculated. Kučan did not meet my expectations. Opposite. They used my statement as if the archbishop and Kučan were pursuing the same policy. Some pastors were very critical of me. I had a good intention that relations between the Church and the state would be regulated as well as possible with the help of President Kučan. He did not participate in this collaboration and disappointed me.

Berlec: In 2004, you were appointed Prefect of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life. Two years later, Pope Benedict XVI. appointed you cardinal. This means that out of all Slovenians, you have reached the highest point in the Vatican hierarchy, or in the Roman Catholic Church. Was it a big responsibility?

Rode: The Congregation for Consecrated Life is one of the most complex and complicated. That is 1.2 million people, each of them has their own rules of life, their own way of life, their own areas of activity, also their origin in this or that country, even in the historical era, which makes a huge difference between the various ancestral communities. To manage all this and to direct them to properly manage their mission, in today’s time, which is full of challenges and dangers, all this represented an extremely demanding task for our congregation, starting, of course, with the task of the prefect. The latter must direct the work of this papal office. On the one hand, there were traditional religious communities, such as the Franciscans, Lazarists, Jesuits, Salesians, and the like, and on the other hand, there were many new religious communities that appear day by day and there are a lot of them around the world today. I remember that we had to examine all these new communities to see if it was healthy or if it was just the current enthusiasm of well-intentioned people who, in fact, did not have the talent or charisma from which something positive could then emerge for the Church. The work of the prefect was extremely, extremely demanding.

Berlec: You have worked professionally with several popes or holy fathers. Can you trust us, which one was closest to your heart, or you think he performed his mission best?

Rode: I have a hard time answering. In fact, the dilemma is between two: John Paul II and Benedict XVI. And yet, Benedict and I were the closest, also in terms of thinking, way of looking at the world, in terms of his brilliant intelligence, in terms of his artistic sense, he was an excellent pianist, in terms of artistic and poetic view of the world, the colossal culture that Pope Benedict has. That is why I put Pope Benedict XVI first. The last time I met him was on Easter afternoon in the Vatican Gardens. Now he is very weak, he is in a wheelchair, but at the same time he is still completely fresh. I remember quoting the poetry of St. John of the Cross to him in Spanish, and when I saw him again afterward, he thanked me again for that quote from St. John of the Cross. He said it was the most beautiful thing he had ever heard in his life.

Berlec: And one last question. How do you see the position of the Church in Slovenia today? It seems to me that, like many Churches around the world, it has found itself completely on the defensive. That it is again in a kind of public opinion ghetto… That it lacks self-confidence. That the media, by deliberately amplifying some unnecessary scandals, pushed it completely into a corner.

Rode: The Church is not just the Pope, bishops, priests, religious men, and women. The church is God’s people. The basic population of the Church is Slovene Christian, Slovene Catholic. They have their task. Slovenian Catholics have their task to influence the development of Slovenian society, to introduce or strengthen certain values in this society, which are the values of our European identity. It is the task of Slovenian Christians to live these values first, to bear witness to them and to enforce them in Slovenian society. I can say that to some extent we are also doing this, you are doing it. As a Slovenian citizen, I have every right to say what I think about Slovenian politics, about their actions, I have my opinion and I have every right to express it.

Berlec: How do you comment on the fact that after the last parliamentary elections we again have a centre-left government, actually a socialist government, but before that we had a centre-right government for two years?

Rode: It is hard for me to judge. Undoubtedly, what happened in the last election is a big surprise for everyone. I am in Rome, and I am not in direct contact with Slovenian political reality, but I know that it was a big surprise also for my friends from Ljubljana and Maribor. What will come of it? We already have several examples in our thirty-year history when governments that seemed to be extremely successful and flourishing at the beginning quickly withered, collapsed and that unexpected turns took place.

Biography

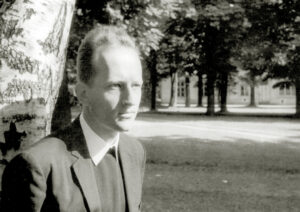

Cardinal Franc Rode was born in 1934 in Ljubljana, he is from Rodica near Domžale. He attended school in nearby Jarše and then in Domžale. In May 1945, he and his family left Slovenia and went to Austria. He continued his education in the refugee camp in Judenburg, then at the high school in Lienz and Spittal near Drava. Like many other families, his family emigrated to Argentina in 1948. In 1952, he entered the theology of the missionary society (Lazarists) in Buenos Aires and in 1957 made his eternal vows. He continued his studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome and at the Catholic Institute in Paris, where he was ordained a priest in 1960. Three years later, he received his doctorate in theology there and returned to Slovenia in 1965, where his first official position was at St. Jožef in Celje. In 1967, he came to Ljubljana and became the director of the Lazarist theologians and later also the superior (visitor) of the Lazarists. At the same time, he became a lecturer at the Faculty of Theology in Ljubljana. After sixteen years of living in his homeland, he went to the Vatican, where in 1981 he took a job in the then papal secretariat for dialogue with non-believers, and until his appointment as archbishop of Ljubljana, he was the secretary of the Pontifical Council for Culture from its foundation in March 1993. In March 1997, Pope John Paul II appointed him Metropolitan Archbishop of Ljubljana. In February 2004, he then appointed him prefect of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, which is considered one of the largest and most demanding offices of the Roman Curia. In early 2006, Pope Benedict XVI appointed him cardinal. Since January 2011, he has been retired prefect of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life. He is the author of numerous professional articles and books and the holder of numerous high honours. Last December, the President of the Republic of Slovenia, Borut Pahor, awarded him with the Golden Order for his life’s work and for his services to the independence of the Republic of Slovenia and its establishment in the world, as well as to the promotion of the culture of interreligious dialogue.

By: Metod Berlec, Vida Kocjan