The summer of 2025 will go down in Slovenian history as the period of the worst traffic jams ever. Motorways turned into stationary traffic jams. The journey between Ljubljana and Maribor took more than three hours instead of an hour and a half, and the journey to the sea took almost three hours as well. An analysis of more than 1.2 million data points prepared by Niko Gamulin reveals that the reason for the collapse was not additional cars, but poorly coordinated roadworks – and, above all, inadequate planning by the Motorway Company in the Republic of Slovenia (DARS) and, ultimately, the state.

The data show that the average speed on motorways drops below 50 kilometres per hour when five or more major works are carried out simultaneously.

The effect is not linear, but exponential: each additional closure triggers a chain reaction that spreads far beyond the immediate area of the works. This means that traffic collapse is not the result of “unavoidable” circumstances, but of wrong decisions in the planning of interventions.

With zero works on the motorway, the average speed is 85.3 kilometres per hour. With one area being under construction, the average speed falls to 76.3 km/h. If there are two cases of roadworks happening simultaneously, the speed falls even lower – to 68.2 km/h. With three cases of roadworks going on simultaneously, the average speed drops to 62.8 km/h, with four, it drops to 54.1 km/h, and with five, it is as low as 48.2 km/h.

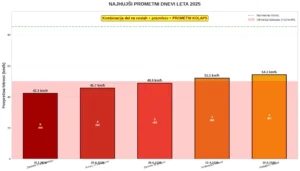

The worst conditions were recorded on the 15th of July, when the average speed dropped to just 42 kilometres per hour. In August, with four major roadworks and the Ferragosto celebrations in Italy, it slipped to 46 kilometres per hour, and in June, at the start of the Slovenian holidays and with five closures, it fell to 49 kilometres per hour.

A particularly important finding of the analysis is that traffic disruptions spread like a wave. At the site of the work itself, the average speed is reduced by about 30 percent, one section away by 19 percent, and two sections away by 11 percent. This means that the consequences of the closure are not local but systemic, as traffic jams can extend three or even four sections away. This spread creates a chain reaction: although the physical closure is limited to a few hundred metres, its effects are spread over tens of kilometres of the road network. Even five sections from the actual site of the roadworks, the speed is still 2.5 percent slower than average.

In some cases, the Motorway Company of the Republic of Slovenia has introduced a so-called 1+1+1 system, where one lane is reserved for emergency vehicles and two lanes are reserved for normal traffic. However, analysis shows that traffic in these cases was almost 60 percent slower than with a classic single-lane closure. The measure, which was supposed to ease traffic flow, has therefore only made the situation worse – by as much as 59 percent!

The Ljubljana Ring Road is particularly critical, as any traffic jams there affect the entire country. The most vulnerable junctions are Kozarje, Malence, Zadobrova, and Koseze. Despite years of warnings about bottlenecks, solutions are being delayed from one study to the next, while those responsible allow congestion to worsen every year.

The consequences for citizens have been enormous. Travel times increased by more than 100 percent during the collapses. The journey from Ljubljana to Koper took two hours and 45 minutes, which is 130 percent longer than usual. The journey to Maribor took three hours and 15 minutes, which is an increase of 117 percent. Drivers needed two and a half hours to get from Kranj to Novo Mesto, which is almost 90 percent longer than the time they would need under normal conditions. These figures are not just statistics, but hours of lost time, additional fuel costs, and logistical delays that affect the economy and people’s daily lives.

However, the traffic collapse was not inevitable. It occurs when uncoordinated roadworks, holiday and festive peaks, accidents, and bad weather coincide. If the works had been spread out and coordinated in terms of timing, the worst traffic jams could have been avoided. However, the Motorway Company of the Republic of Slovenia allowed too many interventions to be carried out at the same time, and the state failed to provide strategic oversight and coordination with other infrastructure projects.

The analysis therefore raises the question of political and managerial responsibility. Who made the decision to carry out the closures at the same time? Why are bad practices, such as the 1+1+1 system, being introduced without verified data? And above all, who will prevent the collapse from happening again next year?

Sara Kovač