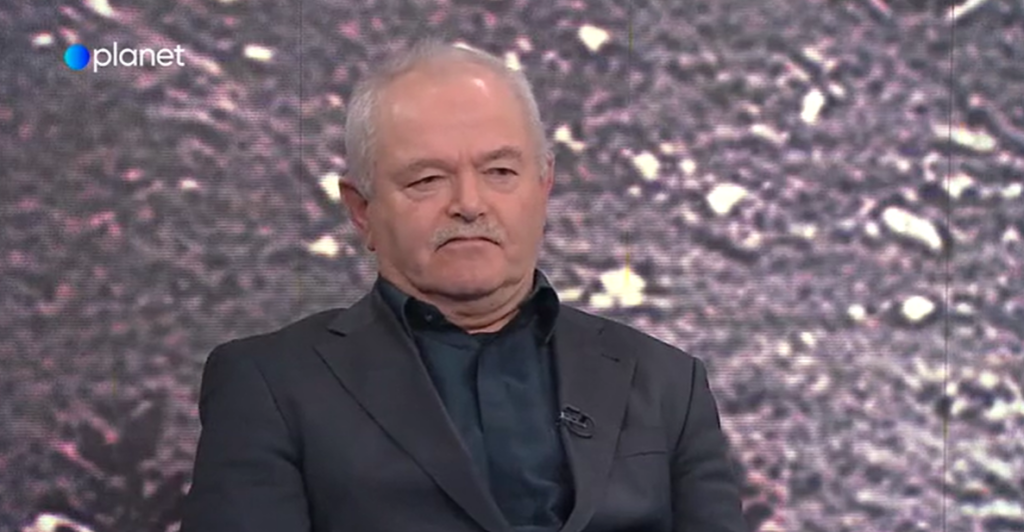

Two more hearings in the Trenta case are scheduled to happen before the end of the year. In this week’s episode of the show “Hour of Power” (“Ura moči”) on Planet TV, Branko Kastelic, the former director of the company Imos and a defendant in the Trenta case, who is accused of damaging his company and thus committing a criminal offence, spoke about his side of the story. “It is clear from all the evidence that I did not do what I am being accused of.”

The company Imos bought the plot from Eurogradnje. This is the company that bought the plot from Janez Janša in 2005. When asked what he is actually accused of as the director of Imos in this indictment, given that it was originally a deal between Janša and the company Eurogradnje, Branko Kastelic explained that the basic accusation was that he had abused his position by signing the contract and that he had, in the words of the prosecution, caused damages to Imos of at least 125 thousand euros. “The facts and all the data show that this is, of course, not true. This is clear from the statutes, from the testimony of the members of the Supervisory Board, and from the procedures by which this contract was signed and about which all the witnesses have testified.” Nor, of course, is it true, he said, that he had caused damages to Imos in this amount, which is evidenced by the accounting data. “This amount is based on an estimate.”

Regarding the history of the deal, he explained that he had a detailed knowledge of it since 2013. “You have to understand that this was one small deal for Imos. At the time I signed it, the contract represented less than one per mille of the annual turnover.” He said he could not remember on what occasion he signed the contract, like many thousands of other documents. He became more familiar with the matter when the affair broke. At that time, he also asked his colleagues to put all these contracts on his desk, which he looked at in detail. He said that he did not know why the company Eurogradnje had bought the plot.

There are many things to be read in the indictment – the claim that Eurogradnje overpaid for the plot in Trenta compared to its real value according to the Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia (GURS) and then that Imos did the same a year later when it paid 10 percent more for it, when it bought the plot from Eurogradnje. Kastelic said that the materials and testimonies of his colleagues show that this purchase procedure was carried out like any other similar procedure. “That is to say, the offer came to us. Nobody remembers how, because 20 years have already passed since then. Then the professional services looked into it, made a proposal to the College and apparently, as the documents show, it was accepted by the College, and the contract was signed after a certain delay. This contract amounted to just over 140 thousand euros.”

“Well, it is also clear from these documents, and I was only made aware of this in recent years, that Eurogradnje made this purchase for something like 10 percent less. Which, looking back over those years, is perfectly understandable to me,” he explained. In 2005, 2006, 2007, there was literally a competition for land purchases. “It happened to us in other locations as well that these prices were rising day by day, and it happened to us several times, and I have given several examples myself, that in one year the prices rose by more than 10 percent,” Kastelic further explained.

When asked whether the purchase by Imos and Eurogradnje was normal for that period, he replied that he is not the only one who believes so. He recalled the time when the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption (KPK) affair broke out, and when he found out that he was also being looked into, since an article appeared in the newspaper Finance, where the transactions of the sales at that time in the Trenta area were listed quite correctly from the Surveying and Mapping Authority application. Based on these sales, he said, the article showed that these sales were roughly in the same range. According to him, it was even stated that the plot was sold a little bit cheaper than usual.

Foto: Posnetek zaslona Planet TVHe flatly denied that he had come to any agreements with Janša

In these charges, Kastelic is accused of having agreed to everything with Janša in advance, because at the time, the then-Prime Minister was buying an apartment from the company Imos. “I categorically deny that I agreed to anything with Janez Janša about this sale and also about the sale of the apartment.” He also told the court that when he found out that the then-Prime Minister was buying a flat from them, he took the time to meet and greet him at the location, as recommended by his colleagues. “I think that was appropriate.” As he recalled, the same procedure was followed when selling to various ministers.

Among the accusations, one can also read about Imos’ dealings with Eurogradnje, which was their subcontractor. It is stated that Imos made an advance payment for the construction of apartments in Istria, Croatia, with which Eurogradnje bought Janša’s plot. With this, they want to portray that there was some kind of agreement between the director of Imos and Janša. “The indictment says so,” he confirmed, pointing out that the contract clearly shows who drafted it, who initialled it, and who then gave it to him to sign. “It is clear that this contract was concluded for an apartment building in Fiesa worth just over one million euros, and it is also clear, I think it was a few months before the purchase of this apartment, that an advance payment of around 200 thousand euros would be made to the subcontractor Eurogradnje.” When asked whether this was the normal way of doing business, Kastelic explained that Imos was in exceptional financial shape at the time. “We had some 10 million euros in deposits in the banks alone. The company’s business policy was to manage this money as economically as possible and, where possible, to place it at better prices than in the bank. We know that the deposits were not expensive to operate. These were either advances or payments made in advance of contractual transfers. The finance department was competent to do this, and the finance directors made this clear at the hearings.”

Kastelic also confirmed that their houses and apartments have always been of interest to the political elite. Before he came to the Imos company, he was employed by the construction company Gradbeno podjetje Grosuplje. This means that he has spent 35 years working in real estate. “In both companies, we worked a lot with the state, communicated with ministers, even with prime ministers. I have to say that as much as I knew Janez Janša, I also knew the first Prime Minister Peterle, as well as Drnovšek and Tone Rop. In short, I met all these presidents or prime ministers at least once on some protocol matters, just like Janša.” He also said that, although in such proceedings, the first person to be considered was always the one who had professionally prepared and initialled the case, he believed that he was probably in the spotlight because he was from Grosuplje. “That’s what the prosecutor told me at the first confrontation in 2014.”

The affair arose because of a new application prepared by the Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia, which somehow valued a plot of land in Trenta at only 20 thousand euros, while Imos had bought it for around 140 thousand euros at the time of the purchase. As for the claim that the app was not very realistic about the value of real estate on the market, Kastelic explained that at the time, he had obtained data on other Imos purchases, compared them with the valuations of the Surveying and Mapping Authority, and on 14 separate occasions it tuned out that in all of these cases, the purchase prices were multiples of the Surveying and Mapping Authority’s valuations. “They were significantly higher, ranging from 8 to a maximum of even just under 300 times as much. The one in Trenta was around 7 times as high,” he pointed out, adding that he had already shown how unrealistic the estimates were at the time. He believes that the appraisers and the prosecutor agree, because no one else is pointing this out. He also mentioned a personal transaction where he had paid 100 thousand euros for agricultural land near Grosuplje, whereas according to the Surveying and Mapping Authority, the estimate of the price was one thousand euros.

According to Kastelic, the case was already somewhat close to its end in 2014, when the valuations by two different appraisers differed by some ten percent on what the land was worth. “Following the court order, an appraiser was appointed, and in parallel, the defence also ordered an appraisal. The two valuations did not differ significantly. Both appraisers said that this was within normal circumstances, they ranged between 120 and 140 thousand euros.” The affair quieted down for a few months, and he believed that the case would not go to court and that there would be no hearings. “The media stopped writing about it. It was no longer interesting because the valuations were very similar to each other,” he said.

Then, with the bankruptcy of Imos, a turning point happened. Suddenly, the focus shifted to stories that the property had been valued at 17,000 euros by the appraiser Zorko for the purposes of the bankruptcy, which was the basis for the renewed prosecution of Kastelic, Janša and the former director of Eurogradnje. Kastelic recalled that the court then appointed one commission. This valuation was already made after the public auction had been carried out on the basis of this valuation of 17,000 euros. The valuation of the first commission was somewhere around the level of the bankruptcy valuation – namely, around 20,000 euros. However, this commission was subsequently disqualified, not because of its substantive comments, but because it was alleged that this commission was somehow politically incorrect. A second commission was appointed and the value was reassessed in 2018 at around the same level. As Kastelic noted, this second commission also included a relative of a member of the first commission.

When asked whether he was surprised that the estate was sold from the body of creditors for almost 130 thousand euros, he replied that he was not. “I was surprised, however, when I found out how many bidders were interested in the property.” According to him, the plot had been contaminated by the media hype. When asked if he thought the case started in 2013 because of him or Janša, Kastelic replied that he had somehow got an idea when he and his lawyer went to the National Bureau of Investigation (NPU). “I was, of course, ready to answer all questions at that time,” he said, as he had nothing to hide. However, his lawyer advised him not to say anything because Janez Janša was also involved, and the case would not be concluded at the police level. As he said, he had to listen to the lawyer, and he said nothing. When asked whether he believed that the case would have ended in 2013, when the valuer hired by the court valued the plot at some 120,000 euros, he replied, “I think so.”

He has never defined himself politically

He said that both in his previous job and at Imos, they had worked extensively with the state during the terms of all different governments. “I have never identified myself politically, but the fact that we have worked a lot with the state, and the fact of who has been the one who has led the country the most, especially after 1990, is in itself a sign of which politicians I have worked with the most,” he explained. He and Janša often meet at hearings and talk a little more than in protocol meetings. He did not really know Klemen Gantar all that well until recently. He was their subcontractor, and they knew each other vaguely from the Grosuplje construction company. He says that the latter did not come to Imos as a subcontractor because he was more familiar with one of the members of the Supervisory Board. As Kastelic is accused of being a stakeholder in Eurogradnje, and they are trying to implicate his whole family in the case, he said that he had explained his reasons in court. Gantar had set up the company Eurogradnje, and this had been brought to Kastelic’s attention sometime later by a former colleague from the Grosuplje construction company, who was a founding member of the company. The latter persuaded Kastelic to buy a share in the business. Kastelic said that he thought of his younger son, who was in grammar school at the time. When he graduated from grammar school and went to construction college, he signed the share over to him. “I don’t see what the problem would be here,” he was clear, adding that in recent years, we have seen leaders in key positions in the country owning companies that work with the state, but no one is questioning this.

It was also mentioned on the show that the appraiser Zorko, who valued the plot in Trenta at 17,000 euros, is also involved in the Litijska Street court building affair. “I was not particularly surprised by this, because I did not believe at the time that the valuation was done by chance. What did surprise me was that the auction was then conducted on the basis of the 17,000 euros valuation, despite the fact that there were already valuations in excess of 100,000 euros, despite the fact that the book value was known, despite the fact that certain employees of Imos were also aware of offers from certain buyers who would have paid at least 100,000 euros for the property.”

Janša already announced his impending conviction on the social network X some time ago. When Kastelic was asked what he himself expected to happen, he replied that if he was trying to be optimistic and still believe that the court was fair, then he expected an acquittal. “It is clear from all the evidence that I did not do what I am accused of. On the other side, there is no tangible evidence of any of it, other than this problematic valuation.” To the final question as to whether he believes he is the victim of some attempt at the settling of political score in this country, he replied, “They call it collateral damage.”