In 1990 and 1991, Slovenia was internationally predominantly isolated in its aspirations and efforts for independence. This has somehow been forgotten, or at least obscured in the last two decades. The analysis of the causes will demonstrate the reasons why this happened.

The archives of domestic and foreign media outlets contain many recordings of statements by state and diplomatic representatives of neighbouring and other countries that directly expressed a dislike or open opposition to Slovenian independence.

The most optimistic view that could be heard in our favour was the phrase conceding that Slovenia could become independent, but only in agreement with other republics and the federation. Of course, anyone who stated this knew very well that the consent of the federal authorities, the YPA and most other republics would not be forthcoming.

Despite attempts to forget and obscure this opposition, it is more or less known and thoroughly documented, but unfortunately it has not been sufficiently analysed and elaborated on by historians and those specializing in international relations.

Launch of negative reviews abroad

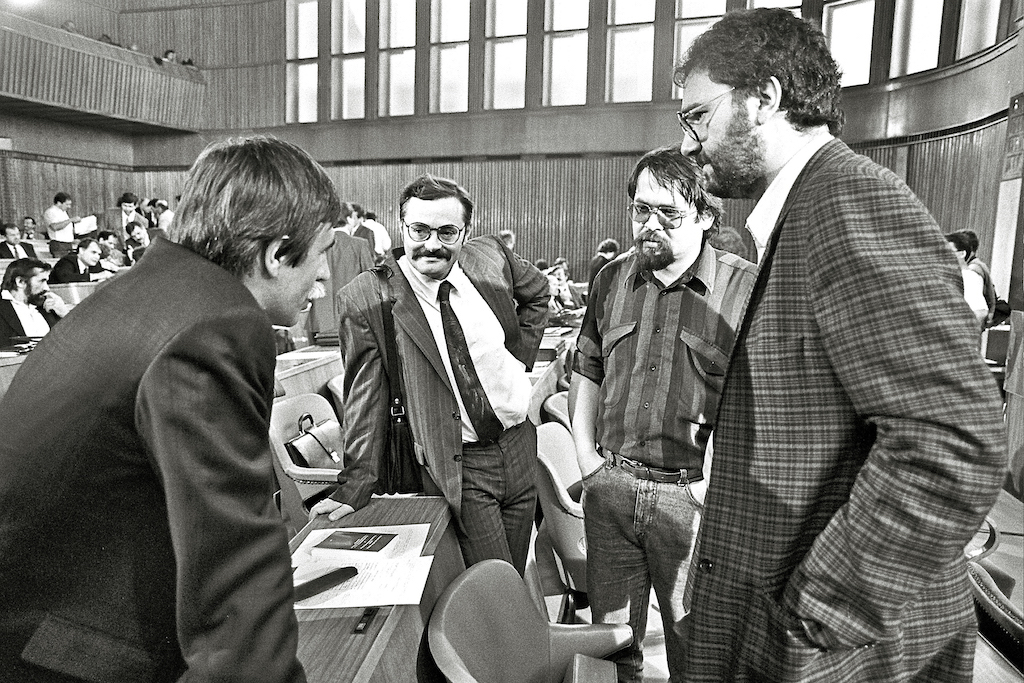

Reports and conclusions made by foreign diplomatic and intelligence representatives are less known. In addition to the scepticism of their governments, especially the personal scepticism of foreign diplomats who followed the events occurring in Slovenia and its neighbouring countries at the time of independence, Slovenians who they had been communicating with, also contributed greatly to the negative reports. Intelligence and diplomatic reports and transcripts of telephone conversations between domestic and foreign services, published in the present almanac, shed light on this aspect. The first shocking finding upon reading them is the realization that nothing was actually hidden from foreigners on the grounds of confidentiality, not even the highest level of state classified information. Even the information regarding the content of the strictly confidential draft of the Constitutional Act on Independence was read to an Italian diplomat by a member of the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia, Ciril Zlobec. The same was true for the carefully guarded date of independence, of which only a few people in the country knew. Members of the then opposition, especially the LDS and today’s SD, were widely communicating their scepticism or even opposition to independence to foreign diplomats and intelligence agents. Some of them, such as LDS MP Franco Juri, then publicly manifested his feelings by boycotting the announcement of the decision on independence, while others, especially successors of the League of Communists of Slovenia (ZKS), spoke differently to the Slovenian public and foreign sources. They both had similar negative attitudes towards all the measures of Slovenian independence, especially the ones related to defence, which were deeply ridiculed. Some examples of such an approach are published in the White Book of Independence – Oppositions, Obstacles, Edition, published in 2013 by the Association for the Values of Slovenian Independence.

Information as a big advantage

From the swearing-in of the Demos government in May 1990 until the final international recognition and acceptance in the UN, the competent Slovenian institutions were attempting to monitor the positions of neighbouring countries, international institutions and the most influential world parties towards Slovenia and its struggle for independence. Due to the scanty beginnings of our own diplomacy, the work was extremely difficult and the most important results were contributed by our compatriots abroad and around the world. Slovenians who served in Yugoslav diplomacy, with a few honourable exceptions, were not in favour of independence, and we received even less useful information from them than from Slovenians in high-ranking positions in the Yugoslav People’s Army.

Information on the views of external parties thus came to us mainly as:

- publicly announced positions of governments and international organizations,

- information of compatriots from abroad and the world,

- contacts of Slovenian state representatives with foreign countries, especially with diplomatic staff of other countries,

- reports from domestic intelligence services,

- reports of foreign services accessed by Slovenia through the work of its own services or through the exchange of information (especially with the Republic of Croatia).

In the Ministry of Defence, the intelligence service was established only at the beginning of the manoeuvring structure of national protection, and for most of this period it numbered less than ten professionally employed members. Despite the weak staff, this service, through patriotic cooperation with individual Slovenians with predominantly lower positions in the YPA, gathered strategically important information that enabled realistic planning of resistance against aggression and the tactically wise implementation of the YPA withdrawal from Slovenia. Through these sources, we also obtained information that foreign diplomatic representatives shared with the YPA summit. In the final stages of independence, especially from the events of May 1991 until the withdrawal of the YPA from Slovenia in October of the same year, the work of the military intelligence service was strengthened. Through the occupation of some YPA communication facilities and the seizure of equipment at the beginning of aggression, the Intelligence and Security Service (OVS) of the Ministry of Defence began to intercept encrypted YPA communications all the way to Belgrade.

After the reorganization at the end of 1990, the Security Information Service (VIS) of the Ministry of the Interior also penetrated some intelligence-rich foreign sources through its own resources, and provided at least a partial direct behind-the-scenes insight into the external environment by controlling communications between foreign services and representatives. From this source, we obtained important information about the extent to which the aggressor, who had excellent access to third-country resources through Yugoslav diplomacy and services abroad, was acquainted with our plans and the actual capabilities of the Slovenian defence. Unfortunately, only a part of the VIS, which numbered in the hundreds of employed, was intimately and professionally in favour of independence. The second and also larger part of VIS remained passive or even opposed. Rather than dealing with the immediate danger, they dealt with everything else possible. Thus, on 25 June 1991, when the declaration of war was issued to Slovenia, the government received an assessment from VIS on the situation in – the Romanian army. A VIS worker guarding a tank barracks in Vrhnika allegedly fell asleep and did not notice that a column of tanks was driving through the door towards Ljubljana. The reason as to how the loud noise of the tank column could not be heard was probably only known in the VIS.

Through the publication of various documents of both domestic services in periodicals and books, the Slovenian public has been able to learn of the many details from behind the scenes of the decisions made on individual aspects of aggression against Slovenia and the attitude of representatives of other countries towards it.

It is unusual, however, that previous publications of the same or similar documents, such as the White Paper on Independence – Oppositions, Obstacles, Publication, did not arouse any special interest from historians or other experts, especially as today in Slovenia there are at least five times more publications than at the time of independence.

Disinterest in some facts and distortion of others

However, although the opposition and obstruction of Slovenian independence from outside and inside has received little interest and even less academic research over the last two decades, much more energy has been invested in persistently belittling the importance of independence. Many events and statements have been silenced or distorted, while others have been particularly highlighted. The distortion of the truth was part of the post-independence routine. The basic guideline was: Everything that shaped the majority value system of the people in Slovenia at the time of independence and democratization at the time of the Slovenian spring, has been relativized and denied. Ever since the plebiscite in December 1990, independence has been constantly denounced as a general reason for all kinds of problems. The slogans were more direct and telling every year, until in 2012 when we experienced banners at the so-called popular uprisings with the inscriptions: “They’ve been stealing from us for 20 years.” or “In 20 years, companies and the state have been stolen from us.” or “20 years of a corrupt political elite is enough”- as if we had lived in heaven before the independence and as if there had been no totalitarian regime in Slovenia in which the country was completely stolen from the people; certainly much more than today, regardless of all the current issues.

Ever since the famous letter written by Kučan in the spring of 1991, there have been attempts to portray the resistance against the disarmament of the TO and the defence of the Slovenian state as an arms trade, and the establishment of state attributes to Slovenia is referred to as the Erased affair. For two decades, the manipulation was so intense that the younger generations growing up during that time could easily learn about the issue of the so-called Erased from the majority of public media; much more extensively than about the measures that enabled the creation of the Slovenian state. Ten years after its creation, the first red star flags appeared at the state celebration on National Day. At first shyly because of the awareness that they represented a symbol of the aggressor army that was defeated in the war for Slovenia, but then more and more aggressively, as if the YPA had won the war. The main point made by the speakers included a sentence that gradually became embedded, which is that without the so-called National Liberation Movement (NOB) there would be no independent Slovenia. It was as if it the sentence was uttered in 1945 rather than in 1991. Thereby, the importance of the independence was erased, or at least diminished when attempts at erasing it did not succeed. When the governments of the transitional left were in power, the state celebration programs on the occasion of the two biggest Slovenian national holidays, Statehood Day, and Independence and Unity Day, were at best empty events, unrelated to the purpose of the national holidays, and at worst, full of open mockery of Slovenia and the values that united us in a successful and joint independence venture.

On the other hand, almost no week in the year went by without pompous and expensive celebrations organized by the Associations of the National Liberation Movement of Slovenia (ZZB), which were full of hate speech and threats to those who were different minded, accompanied with the exhibition of totalitarian symbols, and criminal activity in the form of tampering with official state symbols and illegally carrying and displaying military weapons. The participants in these mass events were mostly paid members of the ZZB, as around 20,000 of them still receive privileged veteran allowances every month, even though many were born after 1945. Privileges had been passed on to descendants in certain cases, as if we had been living under a feudal principality. Such bacchanalia in the style of rallies from Miloševič’s most intense campaign a quarter of a century ago were crowned by the ZZB rally on 24 December 2012 in Tisje, where the general secretary of the veteran’s organization Mitja Klavora, born a decade after World War II, threatened us with massacres again.

For several years after independence, it was necessary to return military decorations with the explanation that the President of the country was not lawfully permitted to award the Sign of Freedom to people who had little to do with independence or even actively opposed it. After ten years, they began to deliberately bring in confusion regarding symbols. On the 15th anniversary of independence, a controversy began over the formation of the Slovenian Army and its age, and on the 20th anniversary, the then President of the Republic even ‘thundered’ over the so-called independence fighters, saying that this “meriting” and transitional clutter should be done with once and for all. Luckily, the majority of voters chose not to re-elect him in the fall of 2012. The final touch of shaming the independence and especially the Slovenian Army was set shortly before the 22nd anniversary with the appointment of the last Minister of Defence.

The so-called ‘Uncles from the Background’ appointed a person to this position who, in 1991, not only indirectly, but actively, through political action and voting, opposed any measures used in the defence of Slovenia against the YPA aggression. “I am not a member of the LDS political party, but I share the same thoughts and views with Roman Jakič,” said YPA Colonel Milan Aksentijević at the assembly, after they obstructed defence preparations together at an utmost critical time. The second chapter of this almanac contains many actual examples of measures obstructing independence, bearing the signature of Roman Jakič and his supporters from the left-wing opposition. If only a few of their amendments to key defence legislation had been adopted, Slovenia would not have been able to successfully defend itself against the aggression of the YPA in June 1991.

Instead of operetta, real military power

This was also the fundamental purpose of destroying all efforts of Slovenia to establish an effective defence system that would be able to withstand the expected and decisive attempt of Belgrade to prevent our independence by force. This is demonstrated in dozens of documents in the White Book of Slovenian Independence. These include the efforts of the Slovenian communist policy of the YPA to disarm the TO, which Dr. Jože Pučnik and Ivan Oman quite rightly described as a betrayal of Slovenia, through the so-called Declaration for Peace, which demanded the rapid unilateral disarmament of Slovenia, and the behind-the-scenes contact with YPA generals and Belgrade politicians, about whom the public learns new information every now and then when the Belgrade archives open or when one of the participants writes a book of memoirs from the opposite side. It was only after a few years, when left-wing politicians tried their best to provide the aggressor general Konrad Kolšek with a Slovenian passport, that it became clear why the formal declaration of war with an ultimatum sent to Slovenia by General Kolšek on the morning of 27 June 1991, which was scattered in the form of leaflets by the YPA planes, was not addressed to the Supreme Commander and President of the Presidency Milan Kučan, but to Prime Minister Lojze Peterle, who under the then constitution virtually had no powers in the field of defence. Due to previous contacts and agreements, Kolšek and other aggressors apparently considered Milan Kučan as one of those that they could count on in the period after the “independence operetta”, when the Demos government would disintegrate due to the effect of a broken leadership and end up in military courts or in front of the firing squad.

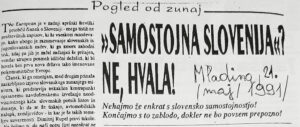

Due to the high support of independence at the plebiscite and the otherwise positive mood towards independence of the Slovenian public – including a faction of members in left-wing parties, opponents of independence generally did not openly oppose it, but rather applied indirect tactics, which was reflected in the slogans that became popular in the spring of 1991, for example “Independence yes, but in a peaceful way.”, or “Independence yes, but without an army.”, or, “The will of the people expressed at the plebiscite must be realized, but only through negotiations and agreements.”, or: “Slovenes did not vote for war in the plebiscite!”, or: “Slovenia’s declaration of independence must go hand in hand with the immediate start of negotiations with other republics on a new confederal connection.”

Furthermore, it was more than only slogans; in the spring of 1991, meetings of Slovenian left-wing parties took place, especially the successor to the ZKS and the predecessor of the then current SD, with the former communist parties in other republics of the former SFRY. One of these meetings that was held between Ciril Ribičič and his comrades with the Bosnian and Croatian communists in Otočec, was accompanied by large newspaper headlines throughout the former Yugoslavia, calling for new Yugoslav integration.

The calculation of the opponents of Slovenian independence, domestic and foreign, was based on the expectation of a broken leadership. They calculated that an independent Slovenia would be euphorically proclaimed, but not realized. (“Dreams are allowed today, tomorrow is a new day!”) They believed and tried to contribute to this as much as possible in belief that the Slovenian Defence Forces would not be able to occupy border crossings and key infrastructure points in the country and limit the YPA manoeuvre, and that after a few days it would all turn out like an operetta episode, after which it would be clear to everyone in the country that we were isolated from the West, that we did not control our own territory and that no one would help us, that no one would recognize us, and that we were hitting our heads into a concrete wall.

After such an outcome, the disintegration of the Demos coalition and the fall of the government, followed by a full takeover of power was expected. They also surely expected the end of the dream of an independent Slovenia, seeing themselves as saviours of Slovenians against dangerous Demos adventurers. Or, as the president of the then LDS said, “It is better to negotiate for an independent Slovenia for a hundred years than to fight for one day.”

These expectations are literally confirmed by the memoirs of the then Prime Minister, Ante Marković, also published in the following section of the present almanac, regarding the meeting between him and the Slovenian left-wing opposition just before the war, on 12 June 1991:

“Marković’s conversation with the opposition gave a common assessment that the contradictions in the ruling Demos are such that only 26 June keeps it together. If nothing happens on 26 June that could strengthen the Demos circuit, there is not much hope left for the government, or specifically: if a process is launched after 26 June, running simultaneously in both directions, towards independence and reintegration, the Demos government will fall in the summer, or in September at the latest.”

After a meeting with the Slovene left-wing opposition, Marković also convinced Croatian President Franjo Tuđman of the likelihood of such a turn of events in Slovenia. Years later, Tuđman spoke about the operetta war in Slovenia, covering up his support of Marković. However, on 27 June 1991, he broke the promise made and the agreement signed on the joint resistance of the two countries in the event of YPA aggression. Operetta independence was actually carried out by Croatia in June 1991, when it declared independence but did not assume effective power. The price that Croatia paid with its lives for Tuđman’s naivety was enormous.

I myself have witnessed quite a few similar open predictions and hints of Slovenian left-wing politicians, not to mention foreign diplomats. Some in the then presidency of the republic, the Deputy Prime Minister and its Finance Minister, who resigned a few months before the war, and many other “respectable” citizens held a similar belief. I met one of them, who then had a great career in independent Slovenia, just before the war at the Kongresni trg square.

He said to me in a somewhat scornful tone: “For an independent state, you don’t need a vision, but divisions.” I didn’t explain to him that we had that too, because he would not have believed me anyway.

According to the narration and multiple publicly recorded performances of the former member of the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia, Ivan Oman, who was the only one in the presidency to consistently support preparations for the defence against aggression, Dr. Jože Pučnik – in one of the many breaks during the negotiations for the plebiscite law in November 1990 – asked the High Representative of today’s SD why they had been overly complicating and basically opposing all proposals for independence. He replied to him that he should understand that they and their political option did not see a future for themselves in independence.

Since the victory of Demos in the April 1990 elections, the top left-wing Slovenian politicians have been working against the creation of real capacities for independence, regardless of the occasional public pretence. Their most important campaigns by 26 June were:

- Disarmament of the Territorial Defence in May 1990, where they helped the YPA in all possible ways. This is discussed in the first chapter of this almanac.

- The so-called Declaration of Peace in February 1991, which directly demanded the rapid unilateral disarmament in one way or another only “for the armed force of Slovenia”.

- Consistent voting against measures to secure independence (Defence Act, Military Duty Act, Defence Budget) in the Assembly. All of the acts listed were barely passed with a few votes of the Demos majority. This is discussed in the second chapter of this almanac.

- Informing foreign services and diplomats about the top state secrets from the operational plans for independence (exact time, list of functions of the federation that Slovenia intended to effectively take into its own hands).

- The petition for the resignation of the General State Prosecutor Anton Drobnič, which had been sent to the public a few days before the declaration of independent Slovenia under the leadership of Milan Kučan and Spomenka Hribar (she offered it to me to sign in his presidential office). Just before the war, they wanted to further shake up Demos with it, as the petition was signed by some prominent politicians of the SDZ and the Greens of Slovenia.

- Police union strike announcement for 27 June 1991.

On 25 June 1991, Slovenia effectively took over the majority of the former federal competencies (border, customs, monetary policy, airspace control, foreign exchange operations and control) and on 26 June, with general popular support and joy, declared independence. On the same and the following day, it successfully withstood the first wave of aggression, so some left-wing politicians had doubts about the success of their expectation of an “operetta declaration of independence”. Nevertheless, their bosses made every effort to extract selfish petty political benefits from such a situation as well.

Former multiple Minister in the Italian Left Governments (for Justice, Foreign Trade, Deputy Foreign Minister) and High Representative of the Socialist International, Piero Fassino, published a book entitled Out of Passion (Per passione, Milano, 2003), where on page 292 he writes how on 27 June 1991, he visited Milan Kučan and Ciril Ribičič in Ljubljana, and how they begged him (sollecitando) that “the Italian and European left should not give the independence of the former Yugoslav republics to the right”. In the months following this visit, it was the Italian Socialist Foreign Minister, Gianni de Michelis who, as a European politician, uttered the most criticism directed at the expense of Slovenian statehood. He agreed to Slovenia’s European recognition only at the last minute. Even when Italian President Francesco Cossiga visited our country on 17 January 1992, after the European Union had already recognized Slovenia, de Michelis sharply attacked the President for this. Nevertheless, Milan Kučan awarded him the badge of honour of freedom a little later. And he clearly knew the reason why.

It did not turn out as expected for the opponents of Slovenian independence. Slovenia did not suffer a broken leadership. The YPA and all those who, as in the case of the JBTZ process or those rallying for the disarmament of the Slovenian TO, had counted on this projected outcome to do the dirty work for them, crashed into the wall of Slovene determination and serious defence preparations.

Revenge of those from whom the state of SFRY was stolen

The resentment was severe. Instead of honestly admitting that they were wrong, or at least remain silent, influential individuals (they were not prosecuted by anyone for their acts that were on the verge of betrayal or even worse) began launching propaganda campaigns against independence activists immediately after the war and before international recognition, and began overthrowing individual Demos members and then, the government.

On the other hand, individuals who had exposed themselves the most through anti-independence activities or had opposed measures to secure it, regardless of their otherwise professional and personal qualities, experienced rapid personal promotion. When reading the summaries of oppositions, obstructions and general misbehaviour in the Slovenian Parliament at the time of making key independence decisions, or the documents and records in the fourth chapter about forming a pact with the aggressor at the local level and in politics in general, we practically do not come across a single name that would be exposed, in one way or another, to public criticism or even condemnation for actions that history has indisputably confirmed as wrong and even harmful.

The president of the then LDS, Jožef Školč became the Minister of Culture and even the President of the National Assembly; the member of the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia Ciril Zlobec, who revealed a top state secret to foreign services, remained a member of the presidency until the end of his term and even became Vice-President of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts; Ciril Ribičič, who addressed foreign policies against Slovenia’s international recognition, became a constitutional judge and even a member of the Venice International Law Commission. A member of the leadership of Marković’s Social Democratic Union, Rado Bohinc, became the Minister of Science and then Minister of the Interior, later Chancellor of the University of Primorska. Franco Juri and Jaša Zlobec, the most extreme opponents of the Assembly to all necessary measures for independence, became ambassadors of the country which they opposed at the time of her birth. Their ardent accomplice in obstructing independence, Roman Jakič, even became the Minister of Defence. Aurelio Juri became a member of the European Parliament, and Sergij Peljhan became the Minister of Culture. Jože Mencinger, who deserted from the government a few months before the war, saying that he did not believe in independence, became the Chancellor of the University of Ljubljana and the owner of the Bajt Institute. Marko Kranjec, who joined him in desertion, first became ambassador and later governor of the Bank of Slovenia. The list is too long to name them all. Journalists and editors, who sowed doubts or expressed open opposition at the time of independence, also advanced extremely quickly. An equally brilliant career awaited those from academic circles who actively opposed the plebiscite for an independent Slovenia and later independence itself. The sample was also transferred to the economy. In the first wave of privatization, most companies were “privatized” by individuals who had lamented the possibility of Slovenia’s economic survival two years earlier. In the second wave, however, it was these or their descendants who received privileged political loans from state-owned banks. The infamous Veno Karbone alias Neven Borak moved from the office of President Kučan to the office of Prime Minister, then became a protector of the “national interest” under the guise of the competition protector, preventing the arrival of foreign investors and competition for domestic tycoons, and later took the position of grey eminence in the Bank of Slovenia.

Despite a successful independence from Belgrade, dreams of new times were only allowed for one day, and then upside-down promotion mechanisms were established in society. The more someone opposed independence or was sceptical of it and the more someone was family, politically or emotionally attached to the former state of SFRY, the greater his chances for career and political success in independent Slovenia were. They worked tirelessly in miniature, between Triglav and Kolpa, to establish a communist pashaluq, which they had lost between Triglav and Vardar. And to some extent, they succeeded. Today, among all the countries that emerged on the territory of the former SFRY, communist and Yugoslav iconography prevails at many events only in Slovenia, and only in Slovenia do former Yugoslav communist officials still receive special pension supplements.

The campaign to discredit Slovenian independence continues to this day: from accusations of arms trafficking to the so-called Erased and statements by the president of the Association of War Veterans for Slovenia, about how it was independence that had divided the previously united Slovenian nation. The actors of discrediting became more aggressive with each passing year as the memory of the generation that experienced independence directly faded. Anyone who pointed out the manipulations was discredited and ridiculed by the media. The network of the former SDV, with more than 10,000 employees intertwined with the judiciary and police apparatus, parastatal institutions such as the corruption commission or information commissioner, and private detective agencies, has remained aggressively active. However, the media monopoly of the transitional left, which diminished the importance of independence every year and glorified the revolutionary gains of the so-called National Liberation War (NOB), has only strengthened since 1992 after a short lull when it subsided at independence.

Resistance to the distortion of history would be virtually impossible today if it were not for the preservation of documents and records from a good two decades ago, some accurate historians, and the efforts of participants who wrote their memoirs. More or less the same actors who wanted in every way to prevent the revelation of the drastic falsification of history from 1941 onwards, and who daily publicly claimed that they would not let it be distorted (read: they will not allow the truth), did, on the other hand, transfer their methods of distortion from the totalitarian regime to the post-independence era. In defending the distorted history of 1941–1990, the same work was used for the period after 1990. Daily brainwashing occurs through the mass media and the basis of this is contained in comments, symposia, school textbooks and programs, as well as documentaries or quasi-documentary broadcasts. All of this, of course, is paid for with taxpayers’ money.

The foundations of independent Slovenia are the values of the Slovenian spring – the foundation of the SFRY was a crime

The Slovenian Constitution contains the text of the oath which is uttered by all top state officials after election. With the oath, they undertake to “respect the Constitution, act according to their conscience and strive with all their might for the well-being of Slovenia”. The test by which we can determine whether an act, conduct, or program of an individual, group, political party, or political option is truly in accordance with the constitutional oath is quite simple.

When an individual, group, party or political option brings to the forefront and emphasizes the values, events and achievements of Slovenian independence, which put us on the world map and around which Slovenians are by far the most united and unified in their history, then it works according to the text and the spirit of the constitutional oath.

But when an individual, group, party, or political option brings to the fore the events and times that have divided and destroyed us as a nation, it acts contrary to the text and spirit of the constitutional oath. And no time was more destructive for the Slovenian nation than the fratricidal communist revolution, with which the criminal clique took advantage of the difficult period of occupation and the genuine patriotic feelings of the Slovenians to seize power by force. Today, you can easily get to know a man through this litmus paper. No one glorifying the time of the fratricidal war in 1991 was sincerely in favour of independence. For the Slovenian state, which, in spite of the division of politics, was created at that time with the great consent of the people, was a fundamental denial of the bloody foundations of the disintegration of the SFRY.

As we have known for a long time and as can be seen in more detail from the presented documents, we were not all in favour of independence. According to the results of the plebiscite, some 200,000 people and most of the post-communist nomenclature in Slovenia, most of the rest of the former SFRY and most of world politics formally opposed Slovenian independence. Among the 200,000 domestic opponents of independence, there were some 50,000 extremists. Some of them took part in the aggression against Slovenia with weapons in their hands, others disgustedly refused Slovenian citizenship and emigrated from the country after the defeat of the YPA. Some stayed and found refuge in Slovenian left-wing parties. Many who refused Slovenian citizenship and left Slovenia together with the defeated army or even earlier, began to return after a few years, when Slovenia progressed, when other parts of the former Yugoslavia lagged behind and when the average pension in our country was ten times higher than the average pension in Serbia and BiH. At first quietly, then more and more noisily, a group of the so-called erased people began to form. The few hundred justified cases when individuals wanted to regulate the status of a foreigner or even citizenship, but did not succeed for objective reasons, were followed by thousands of speculators, who betrayed Slovenia at the time of its birth and today claim damages from Slovenian taxpayers with the help of anti-Slovenian left-wing policy.

Despite the obstacles, opposition and betrayals, Slovenian independence from Belgrade succeeded. But there was another option …

About the author:

Janez Janša was the Vice-President of the Slovenian Democratic Union, a member of the first democratically elected Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia in 1990 and the Minister of Defence at the time of Slovenia’s independence in 1990−1992. Today, he is the President of the Slovenian Democratic Party and for the third time the Prime Minister of the Republic of Slovenia.

Source: Association for the Values of Slovenian Independence: White Paper on Slovenian Independence – Oppositions, Obstacles, Betrayal. Nova obzorja, d. o. o., Ljubljana 2013.