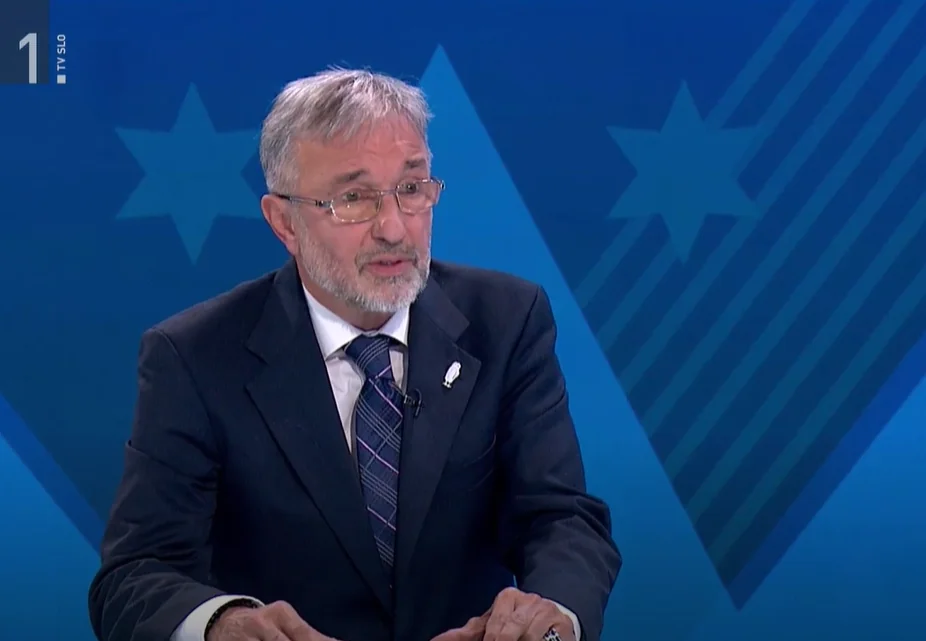

The President of the Supreme Court, Miodrag Đorđević, on the show “Politično” (Political) on state television, problematised the “creation of a psychosis against the judiciary” and labelled all warnings against the “crooked judiciary” as “conspiracy theories” and the like, while the facts expose the many systemic problems of the judiciary.

The judiciary has apparently sensed that after 15 years of judicial bullying, the recent acquittal of opposition leader Janez Janša, and protests against systemic problems in the judiciary, it is time for media sanitisation. The latter followed in a recent episode of the show “Politično,” where the President of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Slovenia said that the politicisation of the judiciary is a problem. The top of the judiciary seems to be in a great panic.

Miodrag Đorđević pointed out that strengthening or even creating a “psychosis against the judiciary” is a serious problem that threatens the fundamental values of the rule of law. In his opinion, criticism of the judiciary that goes beyond the bounds of reason is not only inappropriate, but also harmful. He referred to Janez Janša’s warnings of “a crooked justice” in the Trenta case, and to the same criticism by protesters outside the Celje District Court who gathered there in support of Janša. “In Slovenia, people are tried in courtrooms, not in public,” Đorđević said, reiterating the need to ensure peaceful conditions for judges.

He later confirmed that he trusts the judges as top legal experts who had sworn before they started their work to act impartially and according to their conscience, and meanwhile, he ignored the facts that are the real reason why people have a lack of trust in the fairness and correctness of the judicial system.

What are the real problems of the judiciary?

Eurobarometer surveys have shown that only 11.8 percent of respondents have full confidence in the courts in Slovenia, which is one of the lowest figures in the European Union. The main reasons for this low level of trust are lengthy court proceedings, which can take years, and occasional perceptions of political interference in the judiciary. Although the backlog has been reduced in recent years and is no longer a systemic problem, there are still cases where courts fail to deal with cases in a timely manner, which affects legal certainty.

The appearance of interconnectedness between judges, members of the Judicial Council and other actors (for example, ex-colleagues and partners) is also problematic, creating the impression of bias or a “judiciocracy”. This further undermines public confidence. The causes of low trust are multifaceted, encompassing the judges’ internal independence and the quality of the trials. Historical cases such as the trials of Martin Uhernik and Milko Novič have created further doubts about the fairness of a system where individuals have been wrongly convicted and later acquitted.

There are also questions about the effective digitisation of justice and the accessibility of court procedures, and while progress has been made in these areas, some procedures remain inefficient. Criticisms have also been raised about inequalities in treatment, where allegedly powerful individuals or politically connected persons are favoured over ordinary citizens. This is particularly pronounced in cases involving well-known persons.

The number of complaints to the European Court of Human Rights remains high

According to the Justice Scoreboard, although Slovenia is making progress in digitising justice (e.g. e-commerce, online information), some procedures are still inefficient, especially in less complex cases, which increases administrative barriers. Last but not least, it is also important to note the high number of appeals to the European Court of Human Rights, which we have also repeatedly pointed out – Slovenia has about 100 times more requests for protection at the ECHR per capita compared to countries such as Germany or Austria, which points to systemic shortcomings in the quality of the trial process.

A. H.