The event that marked the undoubted beginning of the Slovenian Spring took place on 16 February 1987 – the 57th issue of Nova revija was published on that day. This issue of the journal was special because it included contributions to the Slovenian National Program, which triggered tectonic shifts.

Already in 1986, after numerous public tribunes of Slovenian intellectuals and writers united in the Slovene Writers’ Association, Nova revija began to prepare a special thematic issue on the situation and goals of the Slovenian nation. This was in stark contrast to the position of the communist authorities, who believed that this program had in fact already been achieved with the NOB and the revolution.

The party reacted with a condemnation

It is interesting that in 1986, Revija 2000 had already prepared a thematic issue on the Slovenian national question, and the editorial board of Nova revija provided a kind of anthology that would set the starting point for the new national program. The list of authors and topics in itself reflected the importance of this project as the special issue of Nova revija contained articles on Slovenian statehood, the Yugoslav “nationalist” crisis, the Slovenian national question, reconciliation, the Slovenian language in the Yugoslav People’s Army, civil society, legal status of Slovenians as a nation, self-determination, Slovenian university, social policy, Christianity in Slovenia and emigration.

The party nomenclature responded immediately. The Central Committee of the ZKS (the League of Communists of Slovenia), which at that time was already headed by the cunning Milan Kučan, decided that it would not respond to the writings of the new journalists with criminal prosecution, but would do everything necessary to prevent the theses outlined in the Slovenian National Program from being realised. However, the forum pressure on Nova revija intensified, as condemnations of the supposedly “bourgeois” and “nationalist” programs came from everywhere, both from the then SR Slovenia and from other parts of Yugoslavia. The communist leadership acted rather cunningly, as it did not prevent the publication of the magazine (which it could have done), but obtained the materials through the secret state police organisation Udba before the publication of the magazine. On this basis, Ciril Ribičič compiled a thirty-page long expertise, and the government also reacted through the SZDL by dismissing both editors of Nova revija, Dimitrij Rupel and Niko Grafenauer.

The path to a new constitution

However, the 57th issue of Nova revija had concrete consequences for later events, especially for the creation of a draft for a new Slovenian constitution, known as the “Writers’ Constitution”. This was otherwise a response to the centralist forces, which demanded an amendment to the constitution that would reduce the power of the republican leadership. In December 1987, Litostroj’s strike took place, which signalled a resistance of the working class against the “avant-garde of the working class”. It was then that, for the first time, a clear demand for the establishment of a new independent social democratic organisation arose. For Udba and the YPA intelligence service, this was a signal that major changes would take place, and the Belgrade military leadership reacted to this with an order to transfer weapons from the border areas to the interior of Slovenia. Non-commissioned officer Ivan Borštner noticed the written order at the Ljubljana command and took a copy to the editorial board of Mladina, the then ZSMS (the Association of Socialist Youth of Slovenia) newspaper, which found itself under severe pressure from the authorities due to critical articles about the YPA and Belgrade politics (“Mamula go home”, “The Night of Long Knives”).

JBTZ as the highlight of the events

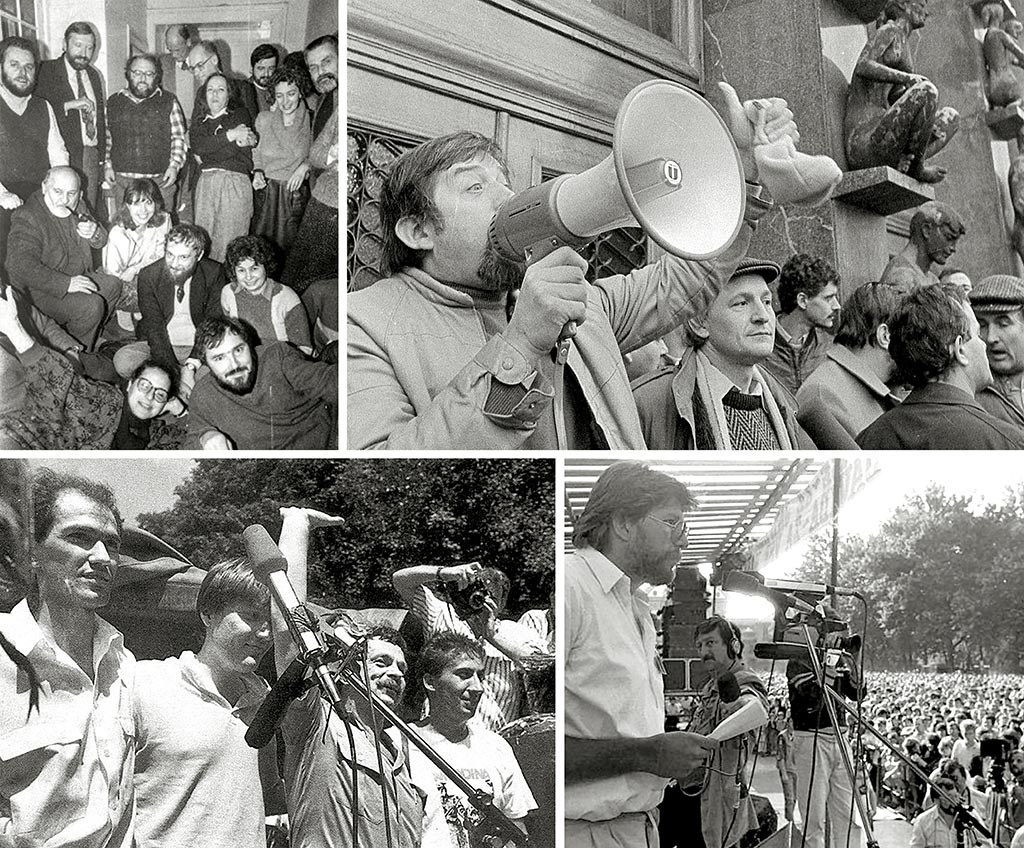

In that hot spring of 1988, many events heralded fateful events for Slovenian history. The assembly of Slovenian farmers was announced, which on 12 May 1988 grew into the establishment of the Slovene Farmers’ Association. Two important pieces were published in the Časopis za kritiko znanosti (Journal for the Critique of Science): “Theses for the Slovenian Constitution” and “Dnevnik in spomini Staneta Kavčiča” (Diary and Memoirs of Stane Kavčič). The authorities only partially reacted to the outcome of the draft constitution, in a similar tone to the 57th issue of Nova revija. The ZSMS congress was announced to be held in the middle of the year, and Janez Janša appeared among the candidates for president, who participated in the publication of Kavčič’s Diary, and as a defence scholar he wrote critically about the YPA. As Belgrade’s pressure on the Slovenian communist leadership to restore order was growing, Slovenian communists opted for a “middle option”: the exemplary arrest of the regime’s most dangerous critics. Therefore, Udba started investigating the premises of MikroAda, where Janša was employed, as it had information that a copy of Borštner had reached him. This is how the construct was composed, which led to the arrest of Janša and Borštner on 31 May 1988, and a little later the editor of Mladina, David Tasič, was also arrested. All three were sent to military custody, the Mladina editor Franci Zavrl defended himself at large, and Igor Bavčar and his colleagues set up a Committee for the Protection of Human Rights, which organised numerous rallies. With the JBTZ affair, the Slovenian Spring broke through the narrow confines of intellectual forums and took to the streets. ZKS had to admit that its scheme, with which it wanted to get rid of Janša forever, had failed.

Gašper Blažič