Avgust Praprotnik was one of the richest Slovenians, who was liquidated by the Intelligence and Security Service (Varnostno-obveščevalna služba – referred to as VOS) in 1942. Years ago, the District Court in Ljubljana finally approved his granddaughter’s request to reopen the criminal proceedings in his case. The Reporter magazine reported that by approving the request, the unjust decision of the District Court in Ljubljana from 1945 was annulled. Namely, with the decision from 1945, the state was able to confiscate the late Praprotnik’s property. However, the District Court in Ljubljana rejected the proposal for the return of the confiscated property – in addition, they explained that in cases where property was confiscated on the basis of articles one and two of the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees, it is not possible to return the confiscated property, based on article 145 of the Enforcement of Criminal Sanctions Act. Does this mean that the decrees of the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia still apply in Slovenian courts?

“After 23 years of abnormal resistance by the state authorities to return the nationalised property to the legal heirs, can we finally expect a fair return of the property which was confiscated after World War II?” Avgust Praprotnik’s great-grandson, Rok Kleindienst, wondered years ago. At the time, the Reporter magazine wrote that the explanation of the District Court of Ljubljana states that the request was approved. In their decision, the members of the senate referred to the decision of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Slovenia, issued on the 12th of March 1998. The decision shows that Article 28 of the Confiscation of Property and Enforcement of Confiscation Act (ZKIK) declared individual persons as war criminals or enemies of the people in criminal proceedings, contrary to the fundamental principles recognised by civilised nations, which also meant that the basic guarantees of a fair trial were not provided. According to the senate, what follows from the decision of the Constitutional Court is that persons who have been wrongly convicted in this way have the right to moral rehabilitation, which they can achieve with the renewal of the court proceedings, under Article 416 of the Criminal Procedure Act, and that they also have the right to have their confiscated property returned to them or their legal heirs.

Praprotnik’s heirs believed that after the rehabilitation of Praprotnik’s image, the decision of the Administrative Court on the 5,613 shares of the Kranjska Industrijska Družba, JSC company, should also have been different. The heirs propose that the proceedings be reopened before the Administrative Court of the Republic of Slovenia. But apparently, something went wrong in 2020. “Decision of the District Court in Ljubljana from 2020. This is a rejection of the claim in the case of the communist robbery of property of the factory owner Praprotnik. The latter was liquidated in 1942 by the VOS. The court refers to the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees (!), which “legalised” all communist theft,” MP Dejan Kaloh wrote on Twitter, appalled. Davorin Kopše wondered whether this means that the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees are still applicable in Slovenian courts, while the government decrees are being serially annulled or restricted in the Administrative and Constitutional Court.

In the decision of the District Court in Ljubljana, we can read that the petitioner’s proposal to return the confiscated property to the late Avgust Praprotnik – 5,290 shares of the Kranjska industrijska družba, JSC company, located in Jesenice and Javornik, in the form of compensation, was rejected. We can also read that the court further clarifies that in cases where the property was confiscated on the basis of articles one and two of the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees, it is not possible to demand the return of the confiscated property, based on article 145 of the Enforcement of Criminal Sanctions Act, and therefore, the ruling in this case (to the extent of the nationalised property under the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees) was meaningless. The court does not deny the right of Avgust Praprotnik Sr.’s successors’ right to demand the return of the property within the nationalised capital share, as well as the return of the nationalised property to the company, due to the rights of the shareholder. However, the manner in which this is exercised, as explained, depends on the legal basis of the final decision in the court proceedings. As the court found that the late Avgust Praprotnik was not entitled to compensation for the confiscated property – 5,290 shares of the Kranjska industrijska družba, JSC company, under the provision of the Enforcement of Criminal Sanctions Act (but was entitled to it under the provisions of the Denationalisation Act, for which an administrative procedure is envisaged), it rejected the proposal in its entirety.

Only the misfortunate become communists, so we must create misfortune

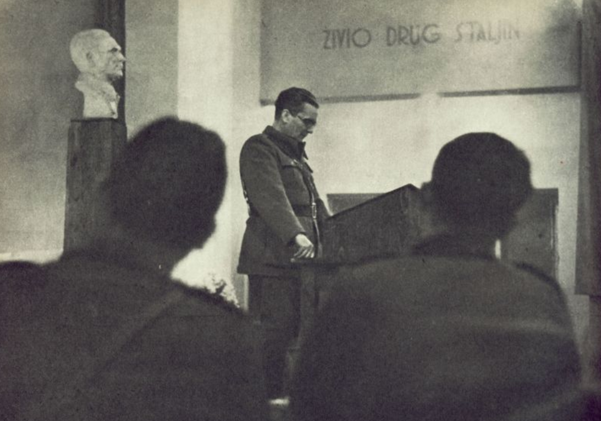

Alojz Kobe also used a quote from Tito’s colleague Moša Pijade, from the first session of the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia in Bihać in 1942, as a reminder. At the time, Pijade said that they had to make so many people homeless that they will become the majority in the country. That way, they would become the masters of the situation. “Those who will have no house, no land, no livestock will quickly join us because we will promise them great war booty. It will be harder with those who own something,” he said, explaining that those who have something are worth nothing to them. “We need to make them homeless, proletarians. Only the misfortunate become communists, so we must create misfortune,” he added, presenting a carefully thought-out plan.

Avgust Praprotnik was a Slovenian banker and entrepreneur. In 1915, he became the director of the Ljubljana branch of Jadranska bank, and when the bank’s headquarters moved to Ljubljana due to the war, he became its deputy director and, in 1920, even the general director. Following the decree of the government of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on the nationalisation of companies owned by Slovene Germans, in 1918, Jadranska bank took over many companies, especially machine factories and foundries. Since the mid-twenties, Praprotnik was one of the leading representatives of industrial entrepreneurship in Slovenia, a member and chairman of various boards of directors, and the head of important economic institutions, associations and federations. Among other things, he was the founder of the Slovene Theatre Consortium and one of the important financial sponsors of the Slovenian People’s Party (SLS). During the occupation of 1941, he became a confidant of the High Commissioner for the Province of Ljubljana (part of the Italian fascist occupation regime from 1941 until the capitulation of Italy in 1942). IN 1942, he was executed by members of the partisan Security and Intelligence Service in a pub on Tavčarjeva Street in the middle of Ljubljana.

Is this really just a matter of procedure?

So, does this mean that the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees still apply in Slovenian courts? One opinion reads: “It means exactly what is written. That, in cases of confiscation of property under the aforementioned articles of the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees, the procedure must be conducted in accordance with the Denationalisation Act and not in accordance with the Enforcement of Criminal Sanctions Act.” Somebody else also explained that this was only a matter of procedure in which a request for the return of property was initiated. “The court explicitly states that claims under the Denationalisation Act are dealt with in administrative proceedings, not with a claim based on the Enforcement of Criminal Sanctions Act. The procedures are determined by the valid Slovenian legislation,” he wrote, adding the phrase “ignorantia iuris nocet” – which means that ignorance of the law burdens the party which should know it. We have not yet learned how the story ended by the time this article was published. But let’s forget about the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia’s decrees for a moment, any confiscation of property should be treated by the courts as a criminal act, and if the culprits can no longer be punished, the injustices should still somehow be settled.

Sara Bertoncelj