Do you still remember the fifteen-year-old Trenta case, which the mainstream media has used against Janez Janša repeatedly? The case deals with a former estate that Janša allegedly sold in in a way that enabled him to gain illegal proceeds – at least according to the political underworld, which has revived the affair several times already, and according to our information, will try to do this once again in the coming days. And the reason for all of this? The failed vote of no confidence that caused the godfathers from the background to go nuts. And, of course, their wish to get rid of Janša – not only from the position of Prime Minister, but from politics in general.

The left-wing part of the opposition, also known as the Constitutional Arch Coalition (Koalicija ustavnega loka – referred to as KUL), will supposedly soon be relieved of some of its burden, due to a resurgence of the affair, which was started fifteen years ago by the prosecutor Boštjan Valenčič, who first sped up and then delayed the case, with the help of the investigating judge Irena Topolšek. The information about this was allegedly communicated by none other than Hinko Jenull, the prosecutor, who is “coincidentally” also the father of the leader of the cycling protests, Jaša Jenull, through the KUL coalition “godfather-on-duty,” Gregor Golobič.

Was the land really worth only eleven thousand euros when it was bought?!

Let’s go back in time for a bit. In 2005, when Janša bought an apartment, he sold his estate in Trenta, known as Tonder’s homestead. The estate is located in Zgornja Trenta, right next to the Soča river, and in total, it measures more than 15.000 square meters. A few years later, the “investigators” from the ranks of the deep state found that they could use the false information about the value, in order to prove to the public that Janša sold the homestead “in ruins” to the company IMOS, which bought the estate, and obtained a purchase price for it, that far exceeded its real value – all of this simply because he was the Prime Minister at the time, which supposedly meant he abused his position. The main players of the Trenta affair managed to do this by simply hiring one appraiser after another through the court, until they finally found the “suitable ones,” meaning, those who estimated that the homestead with the estate was worth more in 1992 than thirteen years later when Janša sold it. Which is completely illogical, given the investments in the estate that were done in the meantime. However, that is not all, because obviously, the socialists do not really understand the logic of the real estate market, as that would mean that, for example, the former skier Jure Košir also gained illegal proceeds when he sold his villa in Bled for a much higher price than the price it was valued at by the Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia, regardless of the fact that the buyer was willing to pay at least a third more for it.

Politically, the affair began in 2011, when the Trenta case was first reported on by journalist Mojca Pašek Šetinc (the instructions were apparently delivered to her by her own husband, who was the politician from the failed LDS party, Milo Šetinc), and Damjanić’s Ninamedia also worked from the background, of course with the intention of Zoran Janković taking over the power that year. However, since Jankovič did not become Prime Minister, and the role once again went to Janša, the famous property report of the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption from 2013 came out, which, of course, burdened Janša (at the time, the Commission was led by Goran Klemenčič, who later became the Minister of Justice in Cerar’s government). The report had concrete political consequences, as Janša’s government later fell because of the vote of no confidence, and Alenka Bratušek became the Prime Minister – she is now once again a member of parliament, following the death of her party colleague Franc Kramar, which left his seat empty. And what did Klemenčič accuse Janša of? He wrote that the estate with the three buildings directly on the bank of the Soča river was only worth eleven thousand euros in 2005, while Janša sold it for as much as 130 thousand euros, which is twelve times more.

Let us just point something out. Plots of land in Trenta are being sold for anywhere between eight and ten euros per square meter, which means that the land alone was worth more than 130 thousand euros. The prosecution, however, claims that a square meter of Tonder’s homestead is worth only about seventy cents.

Perjury, Partia and Trenta

In 2013, a formal judicial investigation of the Trenta case was also launched, almost simultaneously with the Patria case. Apparently, the main players of the political underground seriously believed that Janša would also be convicted in the Trenta case and that this would mean the end of his political career. At the beginning of the investigation, however, the plan failed, as the first appraiser assessed the value of the estate very similarly to the value at the time of sale. As a result, the judge was not happy, and neither was the prosecutor Valenčič, who was being directed from the background by “the father” Jenull.

They kept demanding new appraisers, until one was finally found, who wrote that in 2005, at the time of the greatest prosperity in the real estate market, immediately after Slovenia’s accession to the EU and during the time of the economic boom, the Tonder’s homestead was worth practically less than what it was worth in 1992 when Janša bought it. The prosecutor’s office then allegedly only took this last appraisal into account, which was completely different from all of the other appraisals, however; it came from the Slovenian Association of Appraisers, whose president is a former functionary of the SD party, and thus, charges were pressed. They even called in the Celje prosecutor Stanislav Pinter, to help secretly order an investigation into Janša’s financial situation.

However, it was clear that they would not be able to close the case, so they started procrastinating and apparently, the godfathers also thought that the Trenta case would become obsolete, and the mainstream media will use this as a fact to show that Janša was not able to prove his innocence. After all, ten years will have passed this year since they began firing blind bullets at the case, which they still do from time to time, especially when the SDS party is in power, as the government has to be harassed and divisions among the coalition partners have to be created. So far, they have been unsuccessful.

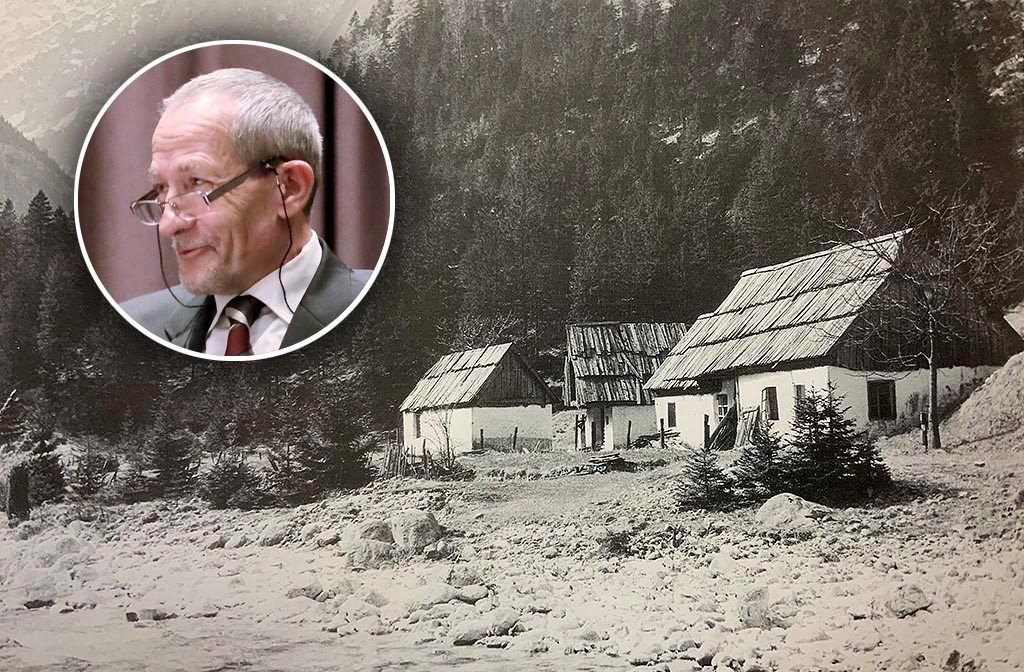

Misleading photographs of Tonder’s homestead

Of course, this does not mean that the media promotion of the Treta affair will stop any time soon. Let us remind you: at the beginning of the affair, President Türk’s adviser, Boštjan Lajovic, took an RTV Slovenia team to the Toner’s estate, and the media then persistently published photos of the ruins of the three buildings, which were in a really bad shape because the new owner did not fix the roofs, and also did not cut down the bushes in the meadows and fields, which were therefore overgrown, after he went bankrupt. And of course, the value of the estate decreased because of that.

However, many photos of Tonder’s homestead from 1952 onwards can be found in books and also online. You can find them in the book called: “Trenta and Soča: Valleys, Mountains and People” (“Trenta in Soča; doline, gore in ljudje”), in which quite a few photos shot by one of the best Slovenian landscape photographers, Jaka Čop, are also published, including a photo of Tonder’s homestead, taken in the 1980s, which clearly shows that the estate has three separate buildings – apparently the appraisers even overlooked one of them. After the estate was sold, both residential buildings still had roofs (the farm’s roof, however, had already collapsed), and there were farmhouse stoves in them. However, the media insist on showing the photos from the time when the estate was already abandoned and poorly maintained.

And what now? It seems that the political underworld, which is directing the KUL coalition, is in desperate need of a new affair that would target Janša, so the prosecutor Jenull has once again stepped in. However, it is not yet known exactly what the new indictment is supposed to refer to, but it will likely represent the next “big bang” in the overthrowing of Janša. Will this perhaps also be the new form of pressuring the SMC party MPs, to do something similar to what Virant’s list did in 2013, to change sides and support the vote of no confidence? One thing is certain. What happened with the appraisers five years ago, brought clear evidence that some of them were politically motivated. For example, Andrej Kocuvan, who was associated with the SD party, as he was elected for the position of a city councillor in Maribor two times, on the list of the aforementioned party. And, of course, Bojan Grum, the court appraiser of the construction profession, the founder of the company Constructa d.o.o., the court appraiser in the Pogorelc and Popovič-Rudonja cases, and the member of several councils of various public institutions in Ljubljana, at the suggestion of Zoran Janković. Bojan Grum’s wife, Darja Kobal Grum, was even a member of the presidency of the then-Liberal (now Alternative) Academy and an LDS candidate in the Ljubljana elections, and the co-author of various publications with Darko Štrajn. And even at the time, most of the investigative bodies primarily dealt with “Janša’s Trenta,” and the managing director of the National Bureau of Investigation at the time, Darko Majhenič, even wrote a criminal complaint against Janša, which helped him secure the position of director at the Bureau of Investigation.

Interestingly, when they were monitoring the banking crimes, for example, the laundering of the Iranian money, the National Bureau of Investigation was nowhere near as devoted and motivated as it was in the Trenta affair. And given the abuses in these procedures – the perpetrators went unpunished – it is not surprising that the history is once again repeating itself, as the farce it is.

Gašper Blažič